publications

Details

Vishwesh Sundar

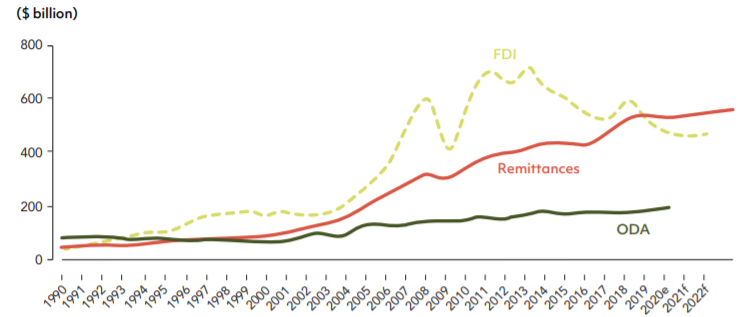

Recently, I had the opportunity to participate in the Global Forum on Remittances, Investment and Development (GFRID). It took place on June 16, 2021 and coincided with the commemoration of the International Day of Family Remittances. In the conference, most speakers highlighted the resilience of remittance flows during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the initial stages of the pandemic, the World Bank had predicted that global remittances were projected to decline by about 20 percent for the year 2020, the sharpest decline in recent history. However, defying the predictions, remittance flows declined only by 2.4 percent, from $719 Billion in 2019 to $702 Billion in 2020. Furthermore, for the low and middle incomes countries, the decline was even more negligible at just 1.6 percent, from $548 Billion in 2019 to $540 Billion in 2020. Compare this to the 12 percent contraction in Foreign Direct Investments inflows to developing countries during the same time.

Figure 1: Remittances, Foreign Direct Investment, and Official Development Assistance Flows to Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 1990–2022 from the World Bank.

These statistics clearly illustrate that during the pandemic, remittances have been a lifeline for millions of people around the world, especially in the Global South. In fact, in some countries such as Pakistan, the inward remittances for the financial year of 2021 swelled, registering record-high numbers. Although, scholars point out that this rise could be due to one-off factors such as the cancellation of the Haj pilgrimage in the case of Pakistan. Upon research, it becomes clear that the reasons for the resilience of remittances are intrinsically related to the motivations of people to remit money.

The literature on the topic indicates that migrants generally remit for three main reasons- altruism, insurance, and investment. Altruistic motivations imply that migrants remit because they gain positive utility from the happiness of their families. For example, during the pandemic, remittance was a lifeline for many migrant households for basic necessities, such as food, housing, education, and healthcare. A related motivation is that of insurance, i.e. remittances that are sent by migrants to their households to protect their families against shocks and risks in their home countries. In addition to the economic shocks created by the pandemic, a remittance increase could be noticed in countries such as Bangladesh, after the floods that hit the country in July 2020. Finally, migrants also remit money to invest in their home countries, i.e. to start a small business or when the exchange rates are favourable. For example, remittance to Mexico increased in the past year due to the depreciation of the peso against the U.S. dollar.

Clearly, as illustrated above, since remittances are intra-familial financial flows, they are more stable, even in the event of a crisis. Migrants remit this money through several means- for example, via bank transfers or using mobile money transfer applications. However, sometimes, they also send money illegally or informally, which are commonly referred to as Hawala transfers. These unofficial transactions are not recorded by the World Bank remittance data. It is estimated that unrecorded flows could be at least 50 percent larger than the recorded flows. A positive, unintended consequence of the pandemic has been that the Hawala-type of businesses were particularly affected due to lockdown restrictions in many countries. This period coincided with the growth of the global digital remittance market. A Forbes report claims that money transfer companies squeezed four years of digital growth into just two months. The increasing competition among the digital remittance service providers due to the new entrants in the industry, as well as the promotional offers provided by some companies to gain market share, has helped drive down transaction costs in several migration corridors. In other cases, migrants have turned to banks that offer SWIFT transfers.

Could this, therefore, mean that the resilience of remittances during the pandemic is slightly inflated, when in fact, a part of the unofficial remittance flows were channeled through formal means, and thus also reflected in the official figures? A World Bank report published in the context of Gambia also seems to echo this view, adding that household surveys in the country indicated that the decline of unofficial remittances were higher than the increase in official remittances, thus resulting in a drop in total remittances. Since there is no data available on the global unofficial remittance flows, it is hard to ascertain its true decline. In any case, the growth in digital financial inclusion of migrants and their households is the need of the hour and should be welcome. As mentioned earlier, the increase in competition among digital remittance service providers could also help drive down the transaction costs closer to the Sustainable Development Goal 10.c of less than three percent, thereby boost the volume of official remittance transactions. It remains to be seen if the migrants would still prefer the digital remittance services over the traditional money transfer services once the pandemic is over.

Author: Vishwesh Sundar is a lecturer of International Relations at Leiden University.